Your doctor may call this cholangiocarcinoma (say: kol-an-gee-oh-car-sin-oh-mah).

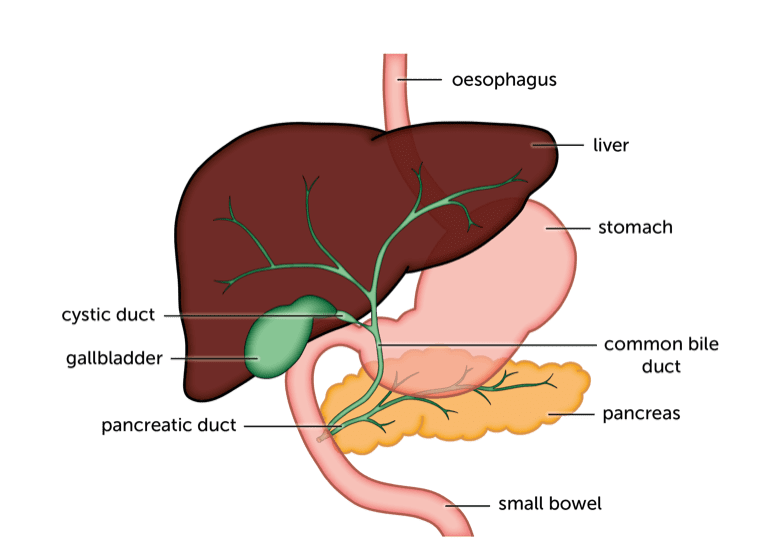

There two main types of bile duct cancer:

- Intrahepatic – bile duct cancer that starts in bile ducts inside the liver

- Extrahepatic – bile duct cancer that starts in bile ducts outside the liver

There are also two types of extrahepatic bile duct cancer – distal and perihilar.

- Perihilar cancers start where the main bile ducts inside the liver meet.

- Distal cancers start in bile ducts that carry bile from the gallbladder to the intestine.

Bile duct cancer symptoms

Early bile duct cancer may not cause any symptoms. Or symptoms may be vague. You may feel sick or lose your appetite.

If the cancer blocks bile ducts, you may develop jaundice (say: jawn-diss). Your skin and eyes may look yellow, caused by bile salts building up in the body. You may also have

- Itching

- dark wee

- pale, putty coloured poo

- flu-like symptoms of muscle aching, fever and tiredness.

Other symptoms include

- losing weight without meaning to

- tummy (abdominal) pain that spreads to your back.

All these symptoms can be caused by other conditions – it’s important to see your GP to find out what’s causing them.

Bile duct cancer risks and causes

About 2,200 people in England are diagnosed with bile duct cancer every year. But it’s still a rare cancer. It doesn’t tend to run in families.

We don’t know what causes most cases of bile duct cancer, but there are some things that increase risk. It’s a myth that liver cancers are always related to alcohol. In fact, it’s unclear whether alcohol is linked to bile duct cancer.

Most people who get bile duct cancer are older, between 50 and 70. Some other liver or gallbladder conditions increase risk because they irritate the bile ducts. People with these may get bile duct cancer when they’re younger than that.

Other factors that may increase risk include

- other liver disease – cirrhosis or long-term infection with hepatitis

- being overweight

- being diabetic

Tests to diagnose bile duct cancer

To start with, most people see their GP who may do some blood tests. If there are any concerns, your GP will refer you to a specialist. At the hospital, you may have any of these scans:

- an ultrasound

- a CT or MRI

- an MRI specifically of your liver and gallbladder (MRCP scan)

You may have one of these tests to look at the area more closely and possibly have a tissue sample taken (biopsy):

- a tube down your throat (endoscopy) to look at your bile ducts from inside the body

- an endoscopy with an internal ultrasound probe (endoscopic ultrasound or EUS)

- an injection of dye into the bile ducts, with a needle put through the skin over the liver (percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography – or PTC)

- an internal examination with a camera put through a small cut (a laparoscopy)

Your doctor will send the biopsy to be checked for signs of cancer. Any cancer cells may be tested for gene changes (mutations). These mutations can help doctors to decide on the best treatments.. The tests are called molecular profiling.

We’re here to help

Talk to a nurse on our helpline:

0800 652 7330

Monday to Friday 10am – 3pm

Alternatively email helpline@britishlivertrust.org.uk

Talk with other people living with liver cancer in our online community.

Bile duct cancer stages

The stage of a cancer means how far it’s grown and whether it’s spread. Doctors decide on treatment according to stage.

In bile duct cancer, you may hear about TNM staging or number staging. TNM stands for Tumour, Node, Metastasis.

T is the size of the cancer.

N explains whether it has spread to nearby lymph nodes (glands).

M means spread to another part of the body.

There are 4 number stages:

- stage 1 is an early cancer, small and localised

- stage2 is slightly bigger, but also localised

- stage 3 has grown outside the liver into nearby tissues or lymph nodes

- stage 4 has spread to another part of the body

There are detailed staging systems for each type of bile duct cancer.

Bile duct cancer treatment

The treatment you’ll have depends on how far the cancer has grown and exactly where it is. The information below is arranged into treatment for different stages of bile duct cancer.

While you’re being treated you will be assigned a clinical nurse specialist. They are your main point of contact and you can call them with questions and concerns, to check on test results, or to talk about your case.

There is also information on check ups and outcomes after treatment for bile duct cancer.

If you have an early cancer, it may be possible to cure it with surgery.

If you have intrahepatic bile duct cancer, you may have part of your liver removed.

If you have extrahepatic bile duct cancer, you’ll have the bile ducts outside the liver and the gallbladder removed. You may need part of your pancreas or small bowel removed as well.

You may have chemotherapy after your surgery, to reduce the risk of the cancer coming back.

If your cancer can’t be removed, your doctor will concentrate on trying to control the cancer and slow its growth. You may have

- chemotherapy

- radiotherapy

- surgery to bypass blocked bile ducts and relieve jaundice

- a small tube (stent) put in to allow bile to flow and relieve jaundice

Read more about treating bile duct cancer that can’t be removed

Often, bile duct cancer is quite advanced when it’s first diagnosed. Unfortunately it can also come back after treatment. Doctors call this recurrent cancer.

Your doctor will focus on trying to control the cancer and relieve any symptoms you have. You may have

- chemotherapy

- radiotherapy

- a targeted (biological therapy)

To relieve symptoms, you may have

- a small tube (stent) put in to allow bile to flow and relieve jaundice

- painkillers, anti-sickness medicines or medicines to relieve itching

Read more about treating advanced or recurrent bile duct cancer

Bile duct cancer check-ups

After your treatment finishes, your doctor will want to see how you are. So you’ll have check ups, or follow up appointments.

After surgery to remove bile duct cancer, you usually see your doctor after a few weeks, then 3 monthly. If all’s well your appointments may become 6 monthly after a couple of years. You may have scans or blood tests from time to time.

If your cancer can’t be removed, you may see your doctor more often during and after treatment. Or, if things are stable, your doctor may suggest you ring if you need an appointment. You don’t have to wait for an appointment if you are concerned or have a new symptom or side effect you’re worried about.

Outcomes (prognosis) for bile duct cancer

It’s difficult for your doctor to tell you how your treatment will turn out. How well people do after a cancer diagnosis depends on:

- how early the cancer is diagnosed

- the treatment you have

- your age, general health and fitness

Statistics for rarer cancers are harder to find. And they are likely to be less reliable because they are based on smaller numbers. We have overall outcome statistics for bile duct cancer. We also have stats for localised, regional and distant bile duct cancer. If you’re not sure, check with your doctor about which group you’re in.

Think carefully about whether you really want to hear the stats. Sometimes people are disappointed that figures aren’t as good as they’d hoped. Response to treatment varies a great deal and you may do a lot better than average. And statistics are always looking at what happened in the past. Patients diagnosed now may do better than patients diagnosed a few years ago.

Living with bile duct cancer

It’s often difficult for people to cope after a diagnosis of cancer. With a rare cancer it can be even harder. You may get tired of explaining your diagnosis. You are less likely to come across people in the same situation as you. Your diagnosis and treatment may take a physical, emotional and psychological toll on you. Added to that, there are practical issues to cope with.

The issues faced by people with bile duct cancer, hepatocellular liver cancer (HCC) and gallbladder cancer are all pretty similar. They are all rare cancers affecting the same area of the body. So we’ve written one section to cover all liver cancer types.

There is information on: